|

| |

|

|

THE

MYTHICAL FORT TEJON "CAMEL CORPS" |

| George

Stammerjohn |

| |

At Fort Tejon,

camels were NOT an essential element of the Fort's

history. Camels were at the Fort for only 5-1/2

months, from Nov. 17, 1859 to mid April 1860. The

camels were never used by the soldiers at Fort

Tejon. They were government property and were kept

here only a short time during the winter of 1859/60

before being moved to the Los Angeles Quartermaster

Depot on their way to Benicia where they were auctioned

off at a loss to the Government in 1864. |

| |

Fort

Tejon was never any "Terminus" for

the camels. There was never a "U.S. Camel

Corps" as has been stated by so many authors;

it was just an experiment. E.F. Beale was a civilian

under contract to survey a road from New Mexico

to California by the U.S. Government. He was

never in command of Fort Tejon, the camels or

any soldiers. |

|

| |

The camels have

been one of the greatest myths and legends of Fort

Tejon's past. The story is great and many writers have

latched on to it. It is great stuff for western lore,

but most stories about this interesting experiment

have little grounding in fact. Unfortunately, many

writers are perpetuating these myths and rely on the

early authors that wrote in the 1920s to 1960s who

based their research and assertions on non-historical

methods. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

THE CAMEL EXPERIMENT

IN CALIFORNIA |

| |

The

victories and settlements of the Mexican-American War

increased the expanse of the territorial United States.

To control and protect this new territory and the new

citizens encompassed within its boundaries or rapidly

moving into the new territories, the government deployed

the vast majority of the U.S. Army. Quickly, Congress

and the War Department became appalled at the unexpected

new cost of simply supplying the outposts scattered

over the new region. The transportation cost of the

Quartermaster Department alone was more than the entire

pre-war budget for the whole of the United States Army. |

| |

Distances

were great, and often now through arid or semi-arid

country. The Army posts, once conveniently established

along waterways and supplied cheaply by contract steamboats,

were now hundreds of miles from water. This meant expensive

civilian contracts with drayage companies or even more

expensive government owned wagon trains managed, operated

and maintained by large numbers of employed civilians,

paid at the prevailing wage - which out west was several

times higher than eastern wages. The expenses seemed

never to stop. Army wagon trains, using mules or oxen,

needed regularly spaced repair, water and feed depots.

Water and feed points were necessary at least a days

journey apart and had to be resupplied either by Army

contract or supply trains. If local farmers could not

deliver forage, hay and grain, to given points, then

the Army had to buy it at one point and stock the feeding

points or it had to carry feed for the animals which

were pulling the freight Wagons. This often meant a

ratio of two forage wagons to every freight wagon.

If a train was outbound for a destination which could

not supply livestock feed for the return journey and

grazing along the route was minimal, then empty wagons

(actually partially loaded wagons for the animals pulling

them had to be fed) would start back for a depot point,

to load up with forage to meet the homeward bound wagon

column. If timely contact was not effected, costly

government mules (or oxen) would die. And the feared

auditors in Washington, D.C. would want to know why. |

| |

Despite

the motion picture image of the western Army on the

frontier, the biggest problems were not "wild

Indians" or "renegade Mexican bandits".

They were transportation, forage, live drayage animals

and a constant demand for economy. |

| |

Spurred

by a hope for improved and economical transport across

the more arid sections of the west, the U.S. Government

dusted off an old plan to experiment with camels as

freight animals. Some 75 Mediterranean camels were

imported in the mid-1850s and delivered to an Army

quartermaster at CampVerde, Texas. |

| |

Fanciful

legend has overshadowed the real story of the camel

experiment. There never was a "Camel Corps";

Edward F. Beale was never appointed to command a camel

corps, and Fort Tejon, California, was never the headquarters

of the non-existent "camel corps." There

is myth and reality about the Army's camels, and the

truth is a more interesting story than the fiction

which surrounds the story. Over developed romantic

fiction has the Army using the camels to haul freight,

regularly to carry the mail, and for active patrols

against bandits and hostile Indians. In reality, very

little of this actually happened or was true. |

| |

|

Gwin

H. Heap |

|

| |

On

trips east across the Great American Desert, Gwin Harris

Heap, a proselytizing convert to the idea of camels

as a cheap transportation methodology for the American

west, foisted upon Edward F. Beale the recently published

book by the Abbe Huc, Travels in Tartary, Tibet and

China, During the Years 1844, 1845 and 1846. While

Beale later claimed be was immediately captivated by

the journal, at the time the opposite was true. It

seemed to have made no impression upon him. In fact,

Beale may have considered Heap somewhat a pushy zealot

of a relative, for they later parted ways under less

than happy circumstances. |

| |

Gwin

Heap became the proponent of camel transportation and

ultimately the buyer of camels when the U.S. Navy was

ordered to acquire camels from Turkey and Egypt and

bring them to Texas. Nowhere in government correspondence

of the time is to be found any advocacy for the use

of camels originating with Edward F. Beale.In fact,

when Beale won the contract for a re-survey and road

development along the 35th Parallel, Secretary of War

John B. Floyd ordered Beale to take 25 camels to California

(and return with them) as part of the expedition. Beale

exploded in anger and in ink to the Secretary. He protested

mightily and insisted that Floyd was wrong to order

him to use the camels. Secretary Floyd stood firm:

he wanted to see what these expensive forage burners,

lounging about Camp Verde outside of San Antonio could

do. Reluctantly Beale, who had no choice, traveled

to Camp Verde, Texas, and picked up the 25 camels. |

| |

The

majority of the foreign laborers hired by the U.S.

Navy to work with the camels were Greek urbanites from

the streets of Constantinople (modern day Istanbul)

who had no experience in the employment of camels.

They had seen a free ride to the United States, where

it was rumored the streets were paved with gold and

it was a true land of flowing milk and honey. The two

Turks who were hired by the Navy, and actually knew

how to handle camels were soon disillusioned by the

flat Texas prairies. They wanted to go home. The Navy

contract specified that all foreigners associated with

the camels coming to Texas were to work six months

and then, if they wished, be discharged, given a bonus,

and transported home for free by the Navy. The two

Turks went home. This meant that the Greeks available

to Beale were absolute novices in handling the camels. |

| |

|

| |

|

ffffffffff |

|

|

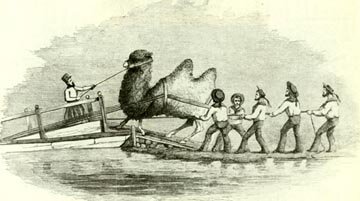

Loading a

Bactrian camel onboard ship in Turkey

Sketch by G. H. Heap, National Archives |

|

Edward F.

Beale |

|

|

| |

"Ned" Beale

soon discovered this flaw, to his anger as his correspondence

to the Secretary of War points out The Greeks seemed

untrainable and totally incompetent, but in time several

mastered their new chore and went on to a long historic,

association with the camels which came west. The others

departed the scene upon arriving in California, leaving

a confusing trail for the historian to follow. Three

of the men had names similar to George (Georgics, Georgious

and Georges) and only one emerged out of the confusion

as "Greek George": Georges Caralambo. |

| |

Two

of the other Greeks also had similar names: Hadji Alli

and Hadagoi Alli. While Hadji Alli became historically

known as "Hi Jolly", the other Alli disappeared

after leaving behind a total confusion caused by the

numerous ways his name could be spelled. All five floated

through the story of the camels until about December

1859, when government records clarified only two were

still in view: "Greek George" and "Hi

Jolly". |

| |

Despite

his initial outrage, Beale did develop an appreciation

of the camels' ability, docility and temperament. He

gained trust in the animals' patience; camels would

not stampede, while mules scattered to the four winds.

The camels did have to be watched. While they would

not run in fright, they would amble about for miles

to feed. By the time Beale's expedition reached California,

Beale was a believer in the camels' worth. |

| |

This

did not mean, however, that Beale was totally honest

in his report to the government over the camels' usefulness.

He failed to report that be had lost three camels,

the expense of which would have been deducted from

the contract's final financial settlement. And he failed

to report that the Mojave Desert's rocky soil nearly

crippled the animals' soft hooves. They were bred for

work in the softer, sand-gravel deserts of the eastern

Mediterranean. |

| |

Beale

also ignored orders to bring the camels back to New

Mexico. Using the lame excuse that the camels would

be invaluable if the troops in California were to become

involved in the "Mormon War", then seeming

to be a reality on the Pacific Coast, Beale left the

camels with his business partner, Samuel A. Bishop,

and hurried home in early January 1858. |

| |

This

homeward journey created another myth, whereby in later

years Beale adopted a heroic leadership which does

not match the historic correspondence of the time.

Once again Beale had outlived the other participants

and this allowed him to tell his version of the story

without eyewitness contradictions. So "the story" became "history". |

| |

As

Beale remembered it, he departed Los Angeles in early

January 1858, with a group of dragoons to protect "him" to

the Colorado River. When he reached the river, "he" stopped

a river steamer and ordered it to ferry him and his

men across the river. "He" had brought along

ten camels to carry forage for his mules and then "he" sent

the camels back to Fort Tejon in case of war in Utah.

It is a great heroic tale and you can find it in all

the biographies on Beale, but it only happened that

way in Beale's imagination, 28 years later. |

| |

While

Beale was moving west in the early fall of 1857, the

U. S. government was moving troops westward against

the Mormon colony in Utah. In California, the Mojave

and Salt Lake Road connected Los Angeles, San Bernardino

and Salt Lake City. The majority of citizens in, southern

California harbored strong anti-Mormon attitudes. While

pending "war news" filtered into California

along the Salt Lake Road, a fantastic set of rumors

emerged that the Mormons departing California were

smuggling tons of firearms toward the Utah colony.

The newspapers reflected these rumors by playing them

to the hilt, often with wild embellishments. Added

to the gunrunning rumors were others, particularly

that Mormon special agents were organizing the desert

Indians to attack "Gentile" parties crossing

the Mojave Desert into southern Utah (now southern

Nevada). |

| |

While

the Army in San Francisco did not put much faith in

these rumors, it decided to launch an investigation.

Major George A. H. Blake, then senior 1st U. S. Dragoon

officer in California, was ordered to take a large

patrol out along the Mojave Road and to examine these

rumors. His orders also included closing the 1st Dragoon

headquarters which had been at Mission San Diego since

August of 1857, and relocating them at Fort Tejon at

the end of the expedition. The Department headquarters

also informed Blake that on the way he should meet

Beale, who was returning east, at Cajon Pass and escort

him as far as the Colorado River. Blake received his

orders in mid-December of 1857 and immediately wrote

an order to 2nd Lieut. John T. Mercer, commanding Company

F at Fort Tejon, to join him at Cajon Pass. |

| |

Major

Blake's orders reached Los Angeles in the midst of

a driving rainstorm, a freak break in weather during

the two year old drought torturing southern California.

First Lieut. William T. Magruder, the commanding officer

at Fort Tejon, was doing Army business in Los Angeles

when the correspondence from San Diego arrived. Despite

the miserable weather, he attempted to return to Fort

Tejon. It took him four muddy days and a broken wagon

to get across the San Fernando Valley. Then, once in

the mountains, he was caught in a wind-whipped blizzard

and nearly lost his way in a world of blowing snow.

On January 2, 1858 he finally managed to reach Fort

Tejon, buried in snow, where he informed Lieut. Mercer

of the task before him. |

| |

Meanwhile,

Beale was in Los Angeles, organizing his return trip.

He had brought ten camels to the pueblo to haul forage

for his mules, leaving the other twelve at Bishop 's

Ranch - not at Fort Tejon. At Mission San Diego, Major

Blake immediately organized his part of the expedition

and, despite the weather, moved out with Dragoon headquarters

staff, band and part of the escort detachment of Company

F troopers left behind when the company had relocated

to Fort Tejon in late August. To guard company and

regimental property at the old Mission, Blake left

a small detachment of many F troopers. He hurried on

his way, assuming that Mercer would also be on the

move. Blake was an impatient, headstrong martinet,

who listened only to his own opinion. He reached Cajon

Pass on New Year's Eve 1858, and gloweringly looked

northward for Mercer's approaching column. As Blake

stood on the eastern flank of Cajon Pass, Mercer had

not even heard yet that he was ordered to join Blake. |

| |

Lieut.

Mercer took his time obeying the orders from Blake.

The weather was impossible. It snowed and snowed and

the snow, driven by terrible winds, piled up ten foot

drifts along the route to Antelope Valley and Los Angeles.

Finally, four days into the new year, Mercer moved

his men out. He did not taDuring 1858, Bishop continued

to use the camels privately. He hauled freight to his

own ranch and to the developing town of Fort Tejon,

located three-fourths of a mile south of the Army post.

He did not haul Army freight, for Phineas Banning of

New San Pedro had won the quartermaster contract once

again. Banning held the contract until the Los Angeles

Depot was finished in mid-1859 and then the Army hauled

its own freight, often with Banning contracted to make

up the shortages in mules and wagons.ajon Pass. He

joined a very angry major Blake on January 10, 1858. |

| |

Edward

F. Beale was also detained by the weather and by the

afternoon of January 10, had not reached Blake 's camp

at Cajon Pass. The next morning, Blake took up the

march over the Mojave Road for the Colorado River.

Beale was at least thirty hours behind Blake and never

caught up. When Blake reached the river he hailed an

exploring river steamer and requested it to wait. Beale

finally arrived, ferried his men and mules over the

Colorado and sent the camels back with Samuel Bishop

to Bishop's ranch in the lower San Joaquin Valley.

Blake, moving fast, led the way back and took his own

command on to Fort Tejon. |

| |

During

1858, Bishop continued to use the camels privately.

He hauled freight to his own ranch and to the developing

town of Fort Tejon, located three-fourths of a mile

south of the Army post. He did not haul Army freight,

for Phineas Banning of New San Pedro had won the quartermaster

contract once again. Banning held the contract until

the Los Angeles Depot was finished in mid-1859 and

then the Army hauled its own freight, often with Banning

contracted to make up the shortages in mules and wagons. |

| |

The

few immigrants to use the poorly developed 35th Parallel

wagon road were harassed by Mojave Indians at the Colorado

Crossing (Beale's Crossing). None of the immigrants

were able to cross and they turned back. To protect

the new route, the government ordered a fort to be

established near the northern crossing of the Colorado

River. |

| |

Major

William Hoffman, 6th U.S. Infantry, led a reconnaissance

in January 1859. He was escorted by dragoons of Companies

K and B from Fort Tejon. There was trouble with Mojaves

at the river; the dragoons killed perhaps a dozen and

Hoffman recommended to San Francisco a full scale campaign

from Fort Yuma against the Mojave Indians. Hoffman

requested a depot be placed at Los Angeles to haul

supplies for his expedition across the desert; the

War Department approved and ordered Captain W. S. Hancock

to Los Angeles. Knowing it would take Hancock time

to organize his wagon trains, Major Hoffman requested

that the Army take charge of the camels and use them

to haul supplies an the desert. The Secretary of War

refused Hoffman's request, stating that the camel experiment

was in the hands of civilians in California and would

remain so. Hoffman's expedition went forth without

the camels. |

| |

In

the meantime, Beale had been ordered by the government

to improve the 35th Parallel wagon road and to do it

right this time. Immigrants had complained about the

road, saying it was not in reality what Beale's propaganda

said it was. For this second expedition, Beale was

assigned 25 more camels, which worked well along the

route. These 25 camels did not cross into California.

At the same time, Bishop was using the original camels

to haul freight for Beale's work crews, and his own. |

| |

Bishop

had several large skirmishes with the Mojave, who were

willing to attack civilians but not the soldiers. Possibly

the skirmish with the dragoons had taught the Mojave

a mild lesson, or it could be they were surprised by

the numbers of soldiers along the river. The civilians

were fewer in number. Hoffman, having fought no Mojave,

concluded peace, established his fort (to become Fort

Mojave) and withdrew, leaving many warlike Mojaves

still out in the desert, eager to kill a white man. |

| |

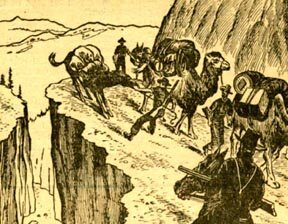

East

of the river, Bishop's men encountered a large force

of Mojaves who showed all signs of wanting an open

battle. Bishop mounted his civilian packers and laborers

onto the camels of this party and charged. They routed

the Mojaves. It was the only camel charge staged in

the west and the Army had nothing to do with it. Then

Bishop moved on eastward to find Beale. |

| |

On

their march home to San Bernardino, Hoffman's troops

ran out of food and allegedly broke into one of Bishop's

buried desert food caches. Three thousand pounds of

food was stolen. Beale was outraged, demanded compensation

and opened a major breach between himself and the Army.

This breach widened and, beginning in the late summer

of 1859, the Quartermaster Department began to demand

that the camels under Bishop's control be turned over

to the Army at Fort Tejon. Finally, on November 17,

1859, Bishop delivered all of the camels but four to

1st Lieutenant Henry B. Davidson of the 1st Dragoons,

regimental and post at Fort Tejon. Davidson hired two

civilians to herd and care for the animals: Hi Jolly

and Greek George. Three of the four missing camels

were found near San Bernardino and finally, after Christmas

of 1859, the fourth was found at Whiskey Flats in the

Kern River gold country. |

| |

|

| "Greek George" |

|

| |

On

November 17, 1859, the Army at Fort Tejon took charge

of the camels from Bishop. The post quickly discovered

that most of the camels were in poor physical shape,

with sore backs, and that it was very expensive to

feed 28 camels on hay and barley. In early March 1860,

they were moved to a rented grazing area 12 miles from

the post, under the care of the two herders, Hi Jolly

and Greek George. |

| |

One

of the government projects for the western experiment

of the camels was to see if they would breed and procreate

in the far western territory. The camels, with males

and females intermixed, proved to the Army that they

could procreate, and produce young, strong, healthy

camels. The herd continued to grow, if slowly. There

is a great deal of nonsense written about the brutality

of Army camel herders to their charges. Camels were

reputedly shot dead, bludgeoned to death, or stabbed

to death by their herders or packers. The Army took

a dim view of herders or packers destroying government

property. Camels were expensive, and if a herder, camel

packer, or soldier had killed a camel, he would have

paid for it by deductions from his salary. An examination

of the salaries of herders, packers, and soldiers in

government employment records revealed no such incident.

The death of each camel (those few that died before

1864, when they were sold) is documented in government

quartermaster records in the National Archives. However,

Beale managed to lose a total of 13 camels and also

managed to escape from paying for the animals. In 1861,

the Army at Fort Smith, Arkansas, was still trying

to get back 10 of the camels sent with Beale on the

second expedition. |

| |

There

is also a great deal of undocumented story-telling

on how Army camels frightened and routed herds of government

horses, overturning wagons or dumping troopers on the

hard ground. Attempts to confirm these stories have

not proven fruitful. Rather, Army reports indicated

how regularly the animals blended together in the same

corrals or fields, and tolerated each other with natural

ease. When the camels were introduced to the government

mule corrals at the Fort Tejon Depot in November 1859,

the quartermaster reported no panic, no tumult; in

fact, he was surprised at how easily the animals adapted

to one another. The camels, showing effects from hard

labor, primarily wanted to eat, and they consumed expensive

oats, barley and hay at alarming rates. |

| |

|

Beale's Adobe

House on the Tejon Indian Reservation

National Archives |

|

| |

Brevet

Major James H. Carleton of Company K, 1st Dragoons,

refused to use the camels for his Mojave River expedition

in the spring of 1860. The camels, having only joined

the Army in November 1859 and moved to a grazing camp

in March 1860, had not yet recovered from the hard

usage of Samuel Bishop, who had worked them to haul

supplies to Beale's road expedition, his ranch, and

to merchants in the civilian town of Fort Tejon from

New San Pedro and Los Angeles. The camels remained

at the grazing camp 12 miles east of the fort under

the care of two civilian herders, and a small detachment

of soldiers to protect the herders, until September

1860. |

| |

The

first official test for camels by the Army in California

was conducted by Captain Winfield S. Hancock, Assistant

Quartermaster in Los Angeles, in an attempt to cut

the expense of messenger service between Los Angeles

and the recently established Fort Mojave on the Colorado

River. This trial, in September 1860, featured the

camel herder Hadji Alli ("Hi Jolly"), riding

a camel like a Pony Express rider, carrying dispatches

for Fort Mojave. One camel dropped dead from exhaustion

at the Fishponds (modern-day Daggett), while a second

attempt to use an "express camel" killed

it at Sugar Loaf (modern-day Barstow). The Army discovered

that while camels died, and it was cheaper, the camels

were no faster than the two-mule buckboard in service

under contract to haul the mail to Fort Mojave. They

also discovered that these camels were not express

animals; they were not bred for speed, but to slowly

carry heavy weights. |

| |

At

the end of September 1860, Hadji Alli and Georges Caralambo

were dropped from Army payrolls, and two former soldiers

were hired as "camel herders" at Fort Tejon,

at a higher salary. Hi jolly was fortunate that he

had been ordered by Captain Hancock to race a camel

to Fort Mojave. He was not held accountable for the

two dead camels and received his full month's pay of

$30.00 for the last month of his employment. Greek

George was fired "for causes", which translated

as stupidity, being unable to read or write, and a

too-frequent fondness for American whiskey. |

| |

The

second experiment, during the early months of 1861,

was again by a government-contracted civilian party.

They were to survey the California-Nevada boundary,

under the leadership of Sylvester Mowry, a former Army

officer and currently a citizen of west New Mexico

Territory. Mowry stayed in Los Angeles fighting a bitter

war with the California State-surveyor and turned the

field work over to J. R. N. Owen. Owen had charge of

four of the camels and hired "Hi Jolly" to

care for them. The expedition went forth to Fort Mojave

with only three camels. |

| |

The

survey was a fiasco, poorly led, poorly organized,

and hopelessly confused. The group was often lost and

never fond the coordinates for the new Nevada-California

boundary line. Instead the expedition drifted into

the northern Mojave Desert and faced disaster in the

barren wilderness. Mules died, equipment was abandoned;

it was only the steady plodding of the camels which

saved the expedition from becoming a fatal exploration

statistic. When they finally struggled over the Sierras

to the village of Visalia it was obvious that the camels

had saved the day. |

| |

At

the end of the survey, the three camels were returned

to Los Angeles. On June 17, 1861, the camels, 31 in

number, of which three were still at the Los Angeles

Quartermaster Depot, were transferred from Fort Tejon

to Captain Hancock at the Los Angeles Depot. There

is no further documentable association of camels with

the later Civil war period at Fort Tejon. |

| |

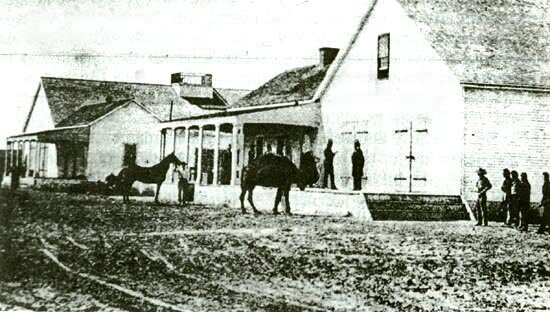

|

The

only known photograph of an Army camel. Government

Depot near Banning's Wharf. |

|

| |

William

McCleave, a former First Sergeant of Company K, 1st

Dragoons, delivered the camel herd to Captain Winfield

S. Hancock on or about the 19th of June 1861. The camels

were placed in the government corrals at the Los Angeles

Quartermaster Depot, where once again they easily mixed

with the government mules. Macleave continued as chief

herder until early August, when Brevet Major James

H. Carleton lured the former sergeant away from Los

Angeles to accept a commission as a Captain in the

forming 1st Battalion of California Cavalry. Emil Fritz,

another former dragoon first sergeant, also traveled

to San Francisco with Carleton to accept a captaincy

in that same battalion. To command the battalion, Carleton,

who would become Colonel of the 1st California Infantry,

gathered in Captain Benjamin Davis of Company K, who

would receive the grade of Lieutenant Colonel of California

Cavalry. Carleton, who was expected to lead an expedition

along the California Trail, wanted his developing cavalry

force commanded by former dragoons. Much to Carleton's

disgust, the Governor appointed a number of men to

be officers in the battalion who did not have mounted

experience. |

| |

When

Carleton and comrades boarded a steamer for San Francisco

in early August 1861, they were joined by Captain Hancock

who had turned over the Los Angeles depot to Second

Lieutenant Samuel McKee of the Dragoon regiment. Hancock,

rumored to have received a staff promotion to the rank

of Major at the San Francisco Quartermaster Department

headquarters, took along his chief clerk, leaving his

office and paperwork in disarray. At San Francisco,

Hancock discovered he was authorized a leave of absence

with War Department permission to seek an Ohio senior

officer's commission. Hancock soon had his general's

star and a command moving from Ohio into western Virginia. |

| |

When

McCleave departed for San Francisco, Charles Smith

also gave up his position as assistant camel herder.

McKee then sought out Hadji Alli and Georges Caralambo

and hired them as camel herders for the depot. When

McKee departed for the east with his regiment, the

camels were left in limbo with Alli and Caralambo looking

out for them. They were moved to Camp Latham, in what

today is Culver City, in early December 1861. |

| |

The next two years

were a period of frustration for the Army on what to

do with the camels, which continued to eat while some

of the females produced healthy young. When the Los

Angeles depot was transferred to Camp Latham and then

to Wilmington on the establishment of Drum Barracks

in February 1862, the camels went along. For a short

period they were the concern of George C. Alexander,

the former sutler or post trader at Fort Tejon, who

was the first senior clerk and financial accountant

at Drum Barracks. Alexander soon gave up the clerkship,

and the post quartermaster office. |

| |

First Lieut. David J. Williamson, 4th Infantry,

California Volunteers, then became the guardian of

the camels. Hadji Alli ("Hi-Jolly") and

Georges Caralambo ("Greek George") continued

to be in charge of direct supervision. The question

was: what to do with the growing and useless herd?

No one wanted, or had time, to bother with them.

Schemes were proposed by the Drum Barracks officers.

A mail express was proposed for the San Pedro to

Fort Yuma run; it was not tried. Then in late 1862

and again in early 1863 there was a proposal, by

Major Clarence Bennett, to carry mail from San Pedro

to Tucson, Arizona. Nothing happened. An irregular

mail express was attempted from San Pedro to Camp

Latham (Culver City) and from Camp Latham on to Los

Angeles. A few trips were made, but then the service

was dropped. Bennett then suggested a mail run to

newly re-opened Fort Mojave on the Colorado River.

The express was tried, but the camel foundered and

died 65 miles from Los Angeles and "Hi-Jolly" once

again carried the mail packet on his back across

the desert on foot to reach the fort on the far side

of the Colorado River.

Major Bennett then proposed sending the camels to Fort

Mojave but Lieut. Williamson, the former acting assistant

at Camp Latham and Drum Barracks, rigorously protested

the move. He could barely feed his own mules, which

were necessary for the operation of the desert fort.

He had no extra forage to feed a small herd of camels.

Furthermore, the camels were unsuited for the rocky

desert roads of the Mojave. The camels' hooves were

too tender; they became lame and were useless. Williamson

declared that Edward Beale had learned this years

ago, but had not reported the truth about his use

of camels on the California desert floor.

At this point Federal Surveyor-General Edward F. Beale

of California and Nevada, from his San Francisco

office, again appeared on the scene. He requested

the use of the camels in order to conduct land surveys

of the uninhabited portions of the new State of Nevada.

Brigadier General George Wright, then in command

of the Department of the Pacific, endorsed Beale's

concept and Lieut. Colonel Edwin B. Babbitt, the

Department' s quartermaster, pondered the suggestion

and then agreed with Wright's opinion. In reality,

Babbitt felt the camels would never be "used

profitably" and as early as November 1862, had

recommended that the experiment be cancelled and

the camels sold. However, Beale's request and the

Army decision to turn the camels over to another

federal agency were kicked upstairs to Washington,

D.C. The Quartermaster General in Washington endorsed

Wright's proposal and Wright was then about to take

action when two separate developments delayed his

decision.

In mid-July 1863, Captain William G. Morris, Assistant

Quartermaster at Wilmington, penned a letter to Colonel

Babbitt. Beale, Morris stated, only wanted part of

the herd and the camels from his experiments had

developed a personality problem. The camels did not

like being used in small groups away from the herd.

They became sulky when separated, refused to eat

or drink, and on reaching a stream of water a camel

would suddenly lie down in it, throwing the rider

and refusing to move. On rocky or gravelly roads

their feet became tender, and very sore. They became

cranky and refused to take commands and often upon

nearing a creek dumped their riders into the water.

In the meantime, Beale was accused of misusing government

funds and of irregularities in conducting surveys.

It would appear that Beale was only surveying property

in which he, or his friends, had a financial interest.

The main charge was that Beale had spent a great

deal of his federal budget on redecorating his own

office in San Francisco. The amount of $64,000 spent

on new carpets and furnishings was bandied about

in anti-Beale circles. Beale was suddenly in disfavor

and General Wright withdrew his support.

In early September 1863, the General in Washington,

D.C. wrote to Colonel Babbitt that the Department of

the Pacific should sell the camels. Babbitt requested

opinions from his quartermasters. Lieutenant Williamson

wrote that the camels were of no use. Again, he stated

the failures of their use at Camp Latham and at San

Pedro. And he reminded Babbbitt that the experiments

by "Lieutenant Beale and his partner Samuel Bishop" showed

that mules were superior. The roads when rough and

rocky crippled the animals. They were only good on

sandy ground. Williamson reminded Babbitt that the

recent trial run of a camel to Fort Mojave had foundered

the animal just 65 miles from Los Angeles, and the

mail carrier had to walk on to Fort Mojave. The express

mail could be carried by "horses or mules with

regularity and with much less expense to the government." Babbitt

was convinced; the camels would be sold at auction

as soon as possible.

A decision was made to sell the camels at auction at

Benicia Arsenal. Obviously too many people in the

Los Angeles area knew their weaknesses and there

was an import market for camels in the San Francisco

area where, after several false starts, a merchant

had been bringing in Siberian camels since 1860.

Captain Morris was informed to prepare to send the

camels northward at the earliest moment, but at the

cheapest method. On November 19, 1863, Morris replied

to Babbitt that the camels, apparently 35 or 37 in

number, were "in first rate condition for the

trip to Benicia Depot." However, he was delayed

in forwarding them due to the heavy winter storms

along the coast route. After two years of terrible

drought, it was raining. Morris also considered that

the current storms would produce grass along the

coastal road, allowing the animals to be fed cheaply

enroute. The camels were started north in late December

1863. For a brief period Morris thought of shipping

them by sea, but the cost of feeding them was unreasonable

and so Morris decided the final answer was to drive

them overland.

The camels reached Santa Barbara on December 30, 1863

and the herders held them there while they celebrated

the coming of the New Year. Then they crossed the

mountains and moved on to the Salinas Valley and

progressed to Mission San Jose. They skirted the

south end of the bay and traveled up the east road

of the shoreline of the Contra Costa, arriving at

the landing site for Martinez on January 17, 18 64.

The next day the camels were ferried across the lower

Carquinez Straits to the government wharf at Benicia

Arsenal and were then moved to the corrals behind

the stone constructed buildings at the Benicia Quartermaster

Depot. They were placed in the open corrals; they

were not stabled in any of the fairly newly buildings

at the depot.1

Auction notices were published and on February 26,

1864, the gavel came down on each camel as a separate

government item. The high bidder for almost all the

camels was Samuel McLeneghan, who reputedly had worked

with the government camels earlier. However, nowhere

in government employment hiring records was McLeneghan's

name found. The 37 camels brought only $1,945, much

to the grief of the Benicia Depot's quartermaster

for be had expected more active bidding and a higher

sales profit. Apparently McLeneghan was the only

bidder, and the auctioneer had trouble getting any

response from the meager crowd that showed up. McLeneghan

got the whole herd for $52.56 each.

The next day, the Benicia quartermaster wrote a report

to his senior in the Department of the Pacific headquarters

in San Francisco. He expressed his regrets that the

total amount of money was so low, explaining that

few of the people who attended were interested in

putting forth money for camels. He had hoped for

more; the auctioneer had tried mightily to encourage

the group of interested or curious spectators, but

at least the camels were sold. The experiment in

California was over. As consolation he offered a

thought of relief: "They have been but a source

of expense for years past."

Author's Note: For years I have worked on the fascinating,

if disappointing, story of the camel experiment in

the West. I have plowed through clouds of myths and

good stories, and have been supported by the ongoing

humor of my colleagues in this business. My friends

have sent numerous new clues, or badly interpreted

or footnoted tales of the camels. But there is one

last tale. Humboldt Lagoons State Park has been one

of my history projects with the Department of Parks

and Recreation and the lagoons are located in Humboldt

County, far away from Fort Tejon, Drum Barracks and

Benicia Arsenal. Yet, the camels haunt me.

In mid-1865, two camels of government vintage were

sold by McLeneghan, or his associates, to the Portland,

Oregon, Zoo. They were placed aboard the ocean going

steamer, the Brother Jonathan, in the same compartment

where George Wright's big black riding horse was

also stabled, and the ship steamed out of San Francisco

for the Columbia River. Off Crescent City the Brother

Jonathan struck a submerged rock and went down, with

only a few of the human passengers surviving. All

the animals aboard were lost. Several weeks later,

on the long sandbar which blocks Stone Lagoon from

the ocean, the bodies of General Wright's horse and

a "Fort Tejon camel" washed ashore. The

local ranchers were forced to bury the stinking carcasses.

One just cannot get away from the Army camels.

The "Camel Barns" at Benicia Arsenal are

not camel barns. The elongated double tiered stone

buildings were "construction buildings" where

the Quartermaster Department manufactured equipment

or altered civilian items purchased on the open market

prior to delivery to the troops in the field. Later,

the buildings were used for storage as warehouses.

|

| |

Sources |

| |

| There are good and bad

descriptions of the camel story. Beginning with those

who tried to be accurate: |

| |

? A Bibliography of the Camel,

California Historical Society Quarterly, December 1930.

? A. A. Gray, "Camels in California",

California Historical Society Quarterly, March 1930.

? Lewis B. Lesley (ed.), Uncle Sam's Camels, the

Journal of May H. Stacey, 1929.

? Woodard, Arthur and P. Griffin, The Story of

El Teion, 1942. A very incomplete and undocumented work.

? Faulk, Odie B., The U.S. Camel Corps, 1976. A

readable but sloppy work. The section an the far west

is filled with errors. |

| |

And

the bad: |

| |

? Howard, Helen

A., "Unique History of Fort Tejon", Journal

of the West. A mythical account; almost nothing is

factual.

? Fowler, Harlan D., Camels in California, 1950.

A cut and paste rip-off of history published by Stanford

University.

? Robertson, Deane and Peggy, Camels in the West,

1979. Riddled with errors.

? California History Commission, Booklet, Drum Barracks

and the Camel Corps. Hilarious collection of errors,

mistakes, and folklore. |

| |

| |

| |

|

|